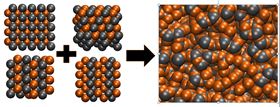

This graphic shows a visual representation of the difference between an organized, crystalline structure and an amorphous glass structure. Image: Eric Perim Martins, Duke University.

This graphic shows a visual representation of the difference between an organized, crystalline structure and an amorphous glass structure. Image: Eric Perim Martins, Duke University.Researchers have discovered a way to predict which alloys will form metallic glasses, potentially paving the way for the development of new strong, conductive materials.

Metallic glasses are sometimes formed when molten metal is cooled too fast for its atoms to arrange themselves in a structured, crystalline order. The result is a material with numerous desirable properties. Because they are metals, metallic glasses boast high hardness and toughness, and good thermal conductivity; because their structure is disorganized, they are also easy to process and shape, and difficult to corrode. Thanks to these characteristics, metallic glasses have found a wide range of uses, including in electrical applications, nuclear reactor engineering, medical industries, structural reinforcement and razor blades.

While metallic glass has been around for decades, scientists have no clue which combinations of elements will form them. As a result, the only way to come up with new metallic glasses to date has been to cook up new recipes in the laboratory with only a few rules of thumb for guidance and hope for the best – a costly endeavor in both time and money.

In a new study, however, researchers from Duke University, in collaboration with groups from Harvard University and Yale University, describe a method that can predict which binary alloys will form metallic glasses. Their technique, which is described in a paper in Nature Communications, involves modelling and comparing the many pockets of different structures and energies that could be found within a solidified alloy.

"When you get a lot of structures forming next to one another that are different but still have similar internal energies, you get a sort of frustration as the material tries to crystalize," explained Eric Perim, a postdoctoral researcher working in the laboratory of Stefano Curtarolo, professor of mechanical engineering and materials science and director of the Center for Materials Genomics at Duke. "The material can't decide which crystalline structure it wants to converge to, and a metallic glass emerges. What we created is basically a measure of that confusion."

To determine the likelihood of an alloy forming a glass, Curtarolo, Perim and their colleagues broke its chemistry down into numerous sections, each containing only a handful of atoms. They then turned to a prototype database to simulate the hundreds of structures each section could potentially take.

Called the AFLOW library, the database stores information on atomic structures that are commonly observed in nature. Using these examples, the program computes what a novel combination of elements would look like with these structures. For example, the atomic structure of sodium chloride – better known as salt – may be used to build a potential structure for copper zirconium.

These simulations produce estimations of characteristics for hundreds of structural forms that a material could take. One characteristic, called an atomic environment, looks at the geometrical arrangement of an atom's closest neighbors. Another calculates the amount of energy stored in each of these atomic structures.

To determine the likelihood of an alloy forming a metallic glass, the program compares these two characteristics for the hundreds of different structures that could be found throughout the material. If groups of atoms near one another have similar energies, they want to form similar structures. But if the rapid cooling prevents this, a metallic glass will emerge.

"The big advantage to our work is that it's high-throughput, because doing this experimentally is way too time-consuming," said Cormac Toher, an assistant research professor in Curtarolo's laboratory. "You cannot check all compositions of all systems in the laboratory. That would literally take forever. The idea behind this is that we can screen a large number of materials in a couple of days and single out the most likely ones that should be checked out."

The group then put their confusion-measuring program to the test to see if it could accurately predict metallic glasses that are already known. They found that the program could correctly identify 73% of known metallic glasses – a number they hope will improve as they continue to increase the structural information and simulations stored in their database.

Based on their initial work, they believe that about one-sixth of the alloys in their system should form metallic glasses. That's more than 250 potential materials, of which only about a couple dozen have been discovered so far.

"If you go to Venice you'll see people blowing bottles of glass," said Curtarolo. "You can do that with metallic glasses as well. You can make lightweight, very durable objects without any seams. But trying to scale these up is difficult. The larger the lump, the longer it takes its center to cool, and the more likely it is to form a normal crystalline structure. But there might be undiscovered chemical combinations that would be easier to work with, cost less, or have other, more desirable properties. We just have to figure out where to look for them."

Besides refining their results for binary alloys, the researchers plan to extend their algorithm to alloys that contain three elements, as they are more likely to form glasses but are much more difficult and time-consuming to model. At the moment, their database has about 10 times more entries for binary alloys than for alloys with three elements.

This story is adapted from material from Duke University, with editorial changes made by Materials Today. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent those of Elsevier. Link to original source.