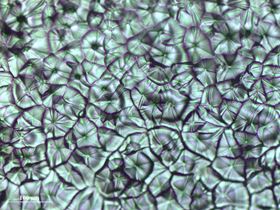

This is an optical micrograph of perovskite crystal grains crafted by the new meniscus-assisted solution printing process. Image: Ming He, Georgia Tech.

This is an optical micrograph of perovskite crystal grains crafted by the new meniscus-assisted solution printing process. Image: Ming He, Georgia Tech.A new low-temperature solution printing technique can fabricate high-efficiency perovskite solar cells with large crystals intended to minimize current-robbing grain boundaries. The meniscus-assisted solution printing (MASP) technique boosts power conversion efficiencies to nearly 20% by controlling crystal size and orientation.

The process, which uses parallel plates to create a meniscus of ink containing the metal halide perovskite precursors, could be scaled up to rapidly generate large areas of dense crystalline film on a variety of substrates, including flexible polymers. Operating parameters for the fabrication process were determined by conducting a detailed kinetics study of perovskite crystals observed throughout their formation and growth cycle.

"We used a meniscus-assisted solution printing technique at low temperature to craft high quality perovskite films with much improved optoelectronic performance," said Zhiqun Lin, a professor in the School of Materials Science and Engineering at the Georgia Institute of Technology. "We began by developing a detailed understanding of crystal growth kinetics that allowed us to know how the preparative parameters should be tuned to optimize fabrication of the films."

The new technique is reported in a paper in Nature Communications. The research has been supported by the US Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFOSR) and the US National Science Foundation (NSF).

Perovskites offer an attractive alternative to traditional materials for capturing electricity from light, but existing fabrication techniques typically produce small crystalline grains with lots of boundaries that trap the electrons produced when photons strike the materials. Existing production techniques for preparing large-grained perovskite films typically require higher temperatures, which is not favorable when polymer materials are used as substrates. But such polymer substrates have major benefits, as they could help lower fabrication costs and produce flexible perovskite solar cells.

So Lin, research scientist Ming He and colleagues decided to try a new approach that relies on capillary action to draw perovskite ink into a meniscus formed between two nearly parallel plates approximately 300µm apart. The bottom plate moves continuously, allowing solvent to evaporate at the meniscus edge to form crystalline perovskite. As the crystals form, fresh ink is drawn into the meniscus using the same physical process that forms a coffee ring on an absorbent surface such as paper.

"Because solvent evaporation triggers the transport of precursors from the inside to the outside, perovskite precursors accumulate at the edge of the meniscus and form a saturated phase," Lin explained. "This saturated phase leads to the nucleation and growth of crystals. Over a large area, we see a flat and uniform film having high crystallinity and dense growth of large crystals."

To establish the optimum settings for the rate for moving the plates, the distance between the plates and the temperature applied to the lower plate, the researchers studied the growth of perovskite crystals during MASP. Using movies taken through an optical microscope to monitor the grains, they discovered that the crystals first grow at a quadratic rate, but slow to a linear rate when they began to impinge on their neighbors.

"When the crystals run into their neighbors, that affects their growth," noted He. "We found that all of the grains we studied followed similar growth dynamics and grew into a continuous film on the substrate."

The MASP process generates relatively large crystals – 20–80µm in diameter – that cover the substrate surface. Having a dense structure with fewer crystals minimizes the gaps that can interrupt the current flow, and reduces the number of boundaries that can trap electrons and positively-charged ‘holes’ and cause them to recombine.

Using films produced with the MASP process, the researchers have built solar cells with power conversion efficiencies averaging 18% – with some as high as 20%. The cells have been tested over more than 100 hours of operation without encapsulation. "The stability of our MASP film is improved because of the high quality of the crystals," Lin said.

Doctor-blading is a conventional perovskite fabrication technique, in which higher temperatures are used to evaporate the solvent. With MASP, by contrast, Lin and his colleagues heated their substrate to only about 60°C, making the process potentially compatible with polymer substrate materials.

So far, the researchers have produced centimeter-scale samples, but they believe the process could be scaled up and applied to flexible substrates, potentially facilitating roll-to-roll continuous processing of the perovskite materials. That could help lower the cost of producing solar cells and other optoelectronic devices.

"The meniscus-assisted solution printing technique would have advantages for flexible solar cells and other applications requiring a low-temperature continuous fabrication process," Lin added. "We expect the process could be scaled up to produce high throughput, large-scale perovskite films."

Among the next steps are fabricating the films on polymer substrates, and evaluating other unique properties (such as thermal and piezotronic) of the material.

This story is adapted from material from the Georgia Institute of Technology, with editorial changes made by Materials Today. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent those of Elsevier. Link to original source.