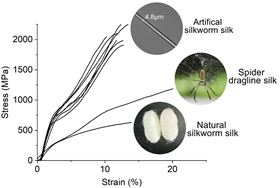

Stress-strain curves of representative artificial and natural silks. Image: Jingxia Wang, Tiantian Fan & Zhi Lin.

Stress-strain curves of representative artificial and natural silks. Image: Jingxia Wang, Tiantian Fan & Zhi Lin.Spiders hold the market for the strongest silks but are too aggressive and territorial to be farmed. The next best alternative involves incorporating spider DNA into silkworms, but this is an expensive and difficult-to-scale process. Now, in a paper in Matter, scientists at Tianjin University in China show how the silk naturally produced by silkworms can be made 70% stronger than spider silks by removing a sticky outer layer and then manually spinning it.

“Our finding reverses the previous perception that silkworm silk cannot compete with spider silks on mechanical performance,” says senior author Zhi Lin, a biochemist at Tianjin University.

Historically, silkworm silk has been used in fashion as a source of luxury robes and apparel fit for royalty, but today silk-based materials are more likely to be found in biomedicine as a material for stitches and surgical mesh. It’s also used for tissue regeneration experiments due to its mechanical properties, biocompatibility and biodegradability.

The most common way to acquire silk is by farming silkworms. However, these silks are weaker and less durable then silk spun by spiders, especially spider dragline silks, which naturally do well under high tension.

“Dragline silk is the main structural silk of a spider web. It is also used as a lifeline for a spider to fall from trees,” says Lin. Silkworms, on the other hand, use their softer silks for the construction of cotton-ball-like cocoons during their transformation into their moth forms.

While other groups have combined DNA from spiders to make silk, Lin’s group wanted to use common silkworms, which are more accessible and easily managed. They were by inspired by the artificial spinning of spider egg-case silk, which is a close relative to silkworm silk and has been shown to do well in the spinning process.

Natural silkworm silk fiber is composed of a core fiber wrapped by silk glue, which interferes with the spinning of the fibers for commercial purposes. To get around this, the researchers boiled silk from the common silkworm Bombyx mori in a bath of chemicals that could dissolve this glue while minimizing the degradation of the silk proteins. Then, to enhance the silk for spinning, the research team solidified the silk in a bath of metals and sugars.

“Since silkworm silk is very structurally similar to egg-case spider silk, which has previously been demonstrated to do well in a mix of zinc and iron baths, we thought to test this alternative method to avoid hazardous conditions used elsewhere,” says Lin. “Sucrose, a form of sugar, may increase the density and viscosity of the coagulation bath, which consequently affects the formation of the fibers.”

Once manually spun and drawn, the silks are thinner than the original silkworm silk, reaching nearly the same size as spider silks. Upon observation under a microscope, Lin describes them as ‘smooth and strong’, indicating that the artificial fibers could withstand force.

“We hope that this work opens up a promising way to produce profitable high-performance artificial silks,” Lin says.

This story is adapted from material from Cell Press, with editorial changes made by Materials Today. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent those of Elsevier. Link to original source.