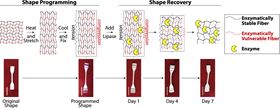

Schematic showing design and operation of enzymatically triggered shape memory polymer (SMP). Composites composed of poly(e-caprolactone) or PCL (red) and Pellethane (black) are heated and stretched. When cooled, the SMP polymer retains its stretched configuration until exposed to enzyme conditions, when it regains its original form.

Schematic showing design and operation of enzymatically triggered shape memory polymer (SMP). Composites composed of poly(e-caprolactone) or PCL (red) and Pellethane (black) are heated and stretched. When cooled, the SMP polymer retains its stretched configuration until exposed to enzyme conditions, when it regains its original form.Researchers from Syracuse and Bucknell Universities have designed a shape memory polymer that responds to biological activity [Buffington et al., Acta Biomaterialia 84 (2019) 88-97, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2018.11.031].

“We have designed the first example of a shape memory polymer that changes its shape in response to enzymatic activity,” explains PhD student Shelby Buffington, who led the work. “[This is] the first SMP that can respond directly to cellular activity.”

Shape memory polymers (SMPs) – or ‘smart’ materials – change their configuration in response to thermal, electrical, or chemical triggers. These materials can return to their original ‘memorized’ shape after being put into a temporary form. Recovery temperatures of most SMPs tend to be too high for biological systems, but more recently photothermally triggered cytocompatible SMPs that can be triggered at or near body temperature have been reported. Such SMPs are helpful in the study of the mechanical behavior of cells, development of bone, cartilage, and nerve tissue engineering, and controlling bacterial biofilms. Until now, however, no SMP triggered directly by biological activity has been reported.

The two-component smart material designed by James H. Henderson’s team comprises poly(e-caprolactone) or PCL and a polyether-based polyurethane thermoplastic called Pellethane, which are, respectively, degraded by enzyme activity and enzymatically stable. The team used electrospinning to create blended fibers from the two polymers, which can be fabricated into flexible mats.

“The blended fiber mats are soft, elastomeric, and show anisotropic mechanical properties due to the aligned nature of the fibers,” says Buffington.

After being stretched into a temporary shape, the material returns to its original configuration when exposed to an enzyme because the shape-fixing component PCL is degraded. The team shows that the SMP composite mats contract in response to enzyme activity without any toxic affects under cell culture conditions.

“The natural crystallinity of PCL holds the temporary shape but as the material is enzymatically degraded the crystallites break up allowing Pellethane, which is a strong elastomer, to recover to its preferred shape,” she explains.

The process is slow, however, with the material taking around a week to revert to its original shape and only at the highest enzymatic concentrations. Nevertheless, the researchers believe the new SMP will have widespread applications since its enzymatic enables it to respond directly to cell behavior.

“For instance, if you placed the enzymatically responsive SMP over a wound, the SMP would apply a tensile force slowly pulling the wound closed as the tissue remodels and the PCL degrades,” points out Buffington.

The findings both introduce a new trigger for SMPs and bring their capabilities to enzyme-responsive materials (ERMs), which are interesting to biological and medical research for applications such as drug delivery, tissue regeneration, stem cell culture, and biosensors.