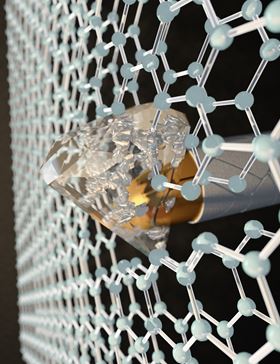

By applying pressure at the nanoscale with an indenter to two layers of graphene, each one-atom thick, CUNY researchers transformed honeycombed graphene into a diamond-like material at room temperature. Image: Ella Maru Studio.

By applying pressure at the nanoscale with an indenter to two layers of graphene, each one-atom thick, CUNY researchers transformed honeycombed graphene into a diamond-like material at room temperature. Image: Ella Maru Studio.Imagine a material as flexible and lightweight as foil that becomes stiff and hard enough to stop a bullet on impact. In a new paper in Nature Nanotechnology, researchers at The City University of New York (CUNY) describe a process for creating diamene: flexible, layered sheets of graphene that temporarily become harder than diamond and impenetrable upon impact.

Scientists at the Advanced Science Research Center (ASRC) at the Graduate Center, CUNY, worked to theorize and test how two layers of graphene – each one-atom thick – could be made to transform into a diamond-like material upon impact at room temperature. The team also found that the moment of conversion resulted in a sudden reduction of electric current, suggesting diamene could have interesting electronic and spintronic properties. The new findings will likely have applications in developing wear-resistant protective coatings and ultra-light bullet-proof films.

"This is the thinnest film with the stiffness and hardness of diamond ever created," said Elisa Riedo, professor of physics at the ASRC and the project's lead researcher. "Previously, when we tested graphite or a single atomic layer of graphene, we would apply pressure and feel a very soft film. But when the graphite film was exactly two-layers thick, all of a sudden we realized that the material under pressure was becoming extremely hard and as stiff, or stiffer, than bulk diamond."

Angelo Bongiorno, associate professor of chemistry at CUNY College of Staten Island and part of the research team, developed the theory for creating diamene. He and his colleagues used atomistic computer simulations to model potential outcomes when pressurizing two honeycomb layers of graphene aligned in different configurations. Riedo and other team members then used an atomic force microscope to apply localized pressure to two-layer graphene on silicon carbide substrates and found perfect agreement with the calculations. Experiment and theory both show that this graphite-diamond transition does not occur for more than two layers of graphene or for a single layer.

"Graphite and diamonds are both made entirely of carbon, but the atoms are arranged differently in each material, giving them distinct properties such as hardness, flexibility and electrical conduction," Bongiorno said. "Our new technique allows us to manipulate graphite so that it can take on the beneficial properties of a diamond under specific conditions."

According to the paper, the research team's successful work opens up possibilities for investigating graphite-to-diamond phase transition in two-dimensional materials. Future research could explore methods for stabilizing the transition and allow for further applications for the resulting materials.

This story is adapted from material from CUNY, with editorial changes made by Materials Today. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent those of Elsevier. Link to original source.