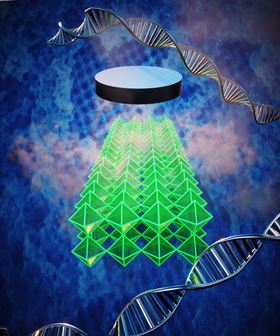

This illustration shows how highly nanostructured 3D superconducting materials can be created by DNA self-assembly. Image: Brookhaven National Laboratory.

This illustration shows how highly nanostructured 3D superconducting materials can be created by DNA self-assembly. Image: Brookhaven National Laboratory.Three-dimensional (3D) nanostructured materials that can conduct electricity without resistance could be used in a range of quantum devices. For example, such 3D superconducting nanostructures could find application in signal amplifiers to enhance the speed and accuracy of quantum computers, and in ultrasensitive magnetic field sensors for medical imaging and subsurface geology mapping. However, traditional fabrication tools such as lithography have been limited to creating 1D and 2D nanostructures like superconducting wires and thin films.

Now, scientists from the US Department of Energy (DOE)'s Brookhaven National Laboratory, Columbia University and Bar-Ilan University in Israel have developed a platform for making 3D superconducting nano-architectures with a prescribed organization. As they report in a paper in Nature Communications, this platform is based on the self-assembly of DNA into desired 3D shapes at the nanoscale. In DNA self-assembly, a single long strand of DNA is folded by shorter complementary 'staple' strands at specific locations – similar to origami, the Japanese art of paper folding.

"Because of its structural programmability, DNA can provide an assembly platform for building designed nanostructures," said co-corresponding author Oleg Gang, leader of the Soft and Bio Nanomaterials Group at Brookhaven Lab's Center for Functional Nanomaterials (CFN) and a professor of chemical engineering and of applied physics and materials science at Columbia Engineering. "However, the fragility of DNA makes it seem unsuitable for functional device fabrication and nanomanufacturing that requires inorganic materials. In this study, we showed how DNA can serve as a scaffold for building 3D nanoscale architectures that can be fully 'converted' into inorganic materials like superconductors."

To make the scaffold, the Brookhaven and Columbia Engineering scientists first designed octahedral-shaped DNA origami 'frames'. Aaron Michelson, Gang's graduate student, applied a DNA-programmable strategy so that these frames would assemble into desired lattices. Then he used a chemistry technique to coat the DNA lattices with silicon dioxide (silica), solidifying the originally soft constructions, which required a liquid environment to preserve their structure.

The team tailored this fabrication process so the structures stayed true to their design, as confirmed by imaging at the CFN Electron Microscopy Facility and small-angle x-ray scattering at the Complex Materials Scattering beamline of Brookhaven's National Synchrotron Light Source II (NSLS-II). These experiments demonstrated that the structural integrity was preserved after they coated the DNA lattices with silica.

"In its original form, DNA is completely unusable for processing with conventional nanotechnology methods," said Gang. "But once we coat the DNA with silica, we have a mechanically robust 3D architecture that we can deposit inorganic materials on using these methods. This is analogous to traditional nanomanufacturing, in which valuable materials are deposited onto flat substrates, typically silicon, to add functionality."

The team shipped the silica-coated DNA lattices from the CFN to Bar-Ilan's Institute of Superconductivity, which is headed by Yosi Yeshurun. Gang and Yeshurun became acquainted a couple years ago, when Gang delivered a seminar on his DNA assembly research. Over the past decade, Yeshrun has been studying the properties of superconductivity at the nanoscale, and thought that Gang's DNA-based approach could provide a solution to a problem he was trying to solve: How can we fabricate superconducting nanoscale structures in three dimensions?

"Previously, making 3D nanosuperconductors involved a very elaborate and difficult process using conventional fabrication techniques," said Yeshurun, a co-corresponding author of the paper. "Here, we found a relatively simple way using Oleg's DNA structures."

At the Institute of Superconductivity, Yeshurun's graduate student Lior Shani evaporated a low-temperature superconductor (niobium) onto a silicon chip containing a small sample of the lattices. The evaporation rate and silicon substrate temperature had to be carefully controlled so that niobium coated the sample but did not penetrate all the way through. If that happened, a short could occur between the electrodes used for the electronic transport measurements.

"We cut a special channel in the substrate to ensure that the current would only go through the sample itself," explained Yeshurun.

The measurements revealed a 3D array of Josephson junctions, or thin non-superconducting barriers through which superconducting current tunnels. Arrays of Josephson junctions are key to leveraging quantum phenomena in practical technologies, such as superconducting quantum interference devices for magnetic field sensing. In 3D, more junctions can be packed into a small volume, increasing device power.

"DNA origami has been producing beautiful and ornate 3D nanoscale structures for almost 15 years, but DNA itself is not necessarily a useful functional material," said Evan Runnerstrom, program manager for materials design at the US Army Combat Capabilities Development Command Army Research Laboratory of the US Army Research Office, which part-funded the work . "What Prof. Gang has shown here is that you can leverage DNA origami as a template to create useful 3D nanostructures of functional materials, like superconducting niobium. This ability to arbitrarily design and fabricate complex 3D-structured functional materials from the bottom-up will accelerate the Army's modernization efforts in areas like sensing, optics and quantum computing."

"We demonstrated a pathway for how complex DNA organizations can be used to create highly nanostructured 3D superconducting materials," said Gang. "This material conversion pathway gives us an ability to make a variety of systems with interesting properties – not only superconductivity but also other electronic, mechanical, optical and catalytic properties. We can envision it as a 'molecular lithography', where the power of DNA programmability is transferred to 3D inorganic nanofabrication."

This story is adapted from material from Brookhaven National Laboratory, with editorial changes made by Materials Today. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent those of Elsevier. Link to original source.