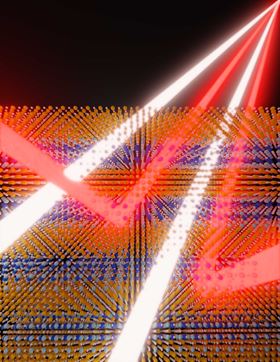

This artist’s rendering shows the novel nanophotonic material reflecting infrared light while letting other wavelengths pass through. Image: Andrej Lenert.

This artist’s rendering shows the novel nanophotonic material reflecting infrared light while letting other wavelengths pass through. Image: Andrej Lenert.A new nanophotonic material has broken records for high-temperature stability, potentially ushering in more efficient electricity production and opening up a variety of new possibilities for the control and conversion of thermal radiation.

Developed by a University of Michigan-led team of chemical and materials science engineers, the novel material can control the flow of infrared radiation and is stable at temperatures of 2000°F in air, a nearly two-fold improvement over existing approaches.

The material uses a phenomenon called destructive interference to reflect infrared energy while letting shorter wavelengths pass through. This could potentially reduce heat waste in thermophotovoltaic cells, which convert heat into electricity but can't use infrared energy, by reflecting infrared waves back into the system. The material could also be useful for various other applications, including optical photovoltaics, thermal imaging, environmental barrier coatings, sensing and camouflage from infrared surveillance devices.

“It's similar to the way butterfly wings use wave interference to get their color,” explained Andrej Lenert, an assistant professor of chemical engineering at the University of Michigan and co-corresponding author of a paper on this work in Nature Photonics. “Butterfly wings are made up of colorless materials, but those materials are structured and patterned in a way that absorbs some wavelengths of white light but reflects others, producing the appearance of color.

“This material does something similar with infrared energy. The challenging part has been preventing breakdown of that color-producing structure under high heat.”

This approach is a major departure from the current state of engineered thermal emitters, which typically use foams and ceramics to limit infrared emissions. These materials are stable at high temperatures but offer very limited control over which wavelengths they let through. Nanophotonics could offer much more tunable control, but past efforts haven't been stable at high temperatures, often melting or oxidizing (the process that forms rust on iron). In addition, many nanophotonic materials only maintain their stability in a vacuum.

The new material works toward solving that problem, besting the previous record for heat resistance among air-stable photonic crystals by more than 900°F in open air. In addition, the material is tunable, allowing researchers to tweak it to modify energy for a wide variety of potential applications. The research team predicted that applying this material to existing thermophotovoltaic cells could increase their efficiency by 10% and believes that much greater efficiency gains will be possible with further optimization.

The team developed the solution by combining chemical engineering and materials science expertise. Lenert's chemical engineering team began by looking for materials that wouldn't mix even if they started to melt.

"The goal is to find materials that will maintain nice, crisp layers that reflect light in the way we want, even when things get very hot," Lenert said. "So we looked for materials with very different crystal structures, because they tend not to want to mix."

The engineers hypothesized that a combination of rock salt and perovskite, a mineral made of calcium and titanium oxides, would fit the bill. Collaborators at the University of Michigan and the University of Virginia ran supercomputer simulations to confirm that this combination was a good bet.

John Heron, an assistant professor of materials science and engineering at the University of Michigan and co-corresponding author of the paper, and Matthew Webb, a doctoral student in materials science and engineering, then carefully deposited the material using pulsed laser deposition to achieve precise layers with smooth interfaces. To make the material even more durable, they used oxides rather than conventional photonic materials – oxides can be layered more precisely and are less likely to degrade under high heat.

"In previous work, traditional materials oxidized under high heat, losing their orderly layered structure," Heron said. "But when you start out with oxides, that degradation has essentially already taken place. That produces increased stability in the final layered structure."

After testing confirmed that the material worked as designed, Sean McSherry, a doctoral student in materials science and engineering at the University of Michigan and first author of the paper, used computer modeling to identify hundreds of other combinations of materials that are also likely to work. While commercial implementation of the material tested in the study is likely years away, the core discovery opens up a new line of research into a variety of other nanophotonic materials that could help future researchers develop a range of new materials for a variety of applications.

This story is adapted from material from the University of Michigan, with editorial changes made by Materials Today. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent those of Elsevier. Link to original source.