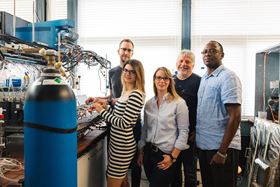

The team at the Center for Electrochemical Sciences at Ruhr-Universität Bochum that developed the novel method: (left to right) Stefan Barwe, Corina Andronescu, Sandra Möller, Wolfgang Schuhmann and Justus Masa. Photo: RUB, Kramer.

The team at the Center for Electrochemical Sciences at Ruhr-Universität Bochum that developed the novel method: (left to right) Stefan Barwe, Corina Andronescu, Sandra Möller, Wolfgang Schuhmann and Justus Masa. Photo: RUB, Kramer.Chemists at Ruhr-Universität Bochum in Germany have developed a novel method for tightly fixing catalyst nanoparticles onto electrode surfaces. Up to now, the high physical stress generated by gas-evolving electrochemical reactions on electrodes has hampered the use of catalyst nanoparticles. Reported in a paper in Angewandte Chemie, this newly-developed method is potentially of interest for the production of hydrogen by water electrolysis.

“Catalyst syntheses often aim for nanoparticles in order to achieve a high surface area,” explains Wolfgang Schuhmann from the Center for Electrochemical Sciences at Ruhr-Universität Bochum. However, tightly fixing nanoparticles onto electrodes has remained a challenge.

Suitable catalyst binders exist for electrodes in acidic media, but these binders are often deployed in alkaline environments because of the lack of suitable alternatives. In alkaline electrolytes, these binder materials are intrinsically unstable and electrically insulating, preventing their use with many highly active and industrially interesting catalyst nanoparticles.

The team from Bochum now proposes a new method for tight fixing catalyst nanoparticles onto metal surfaces. For this, they employed the organic polymer polybenzoxazine, which turns to carbon at temperatures of around 500°C. They applied a mixture of the polymer and catalyst nanoparticles onto the surface of a nickel electrode and heated it to high temperatures, transforming the polymer into a carbon matrix that firmly bound the nanoparticles to the electrode.

The choice of polymer is critical for this novel method. Polybenzoxazines are highly thermal stable and exhibit near-zero shrinkage at high temperatures, while in the absence of oxygen they carbonize giving high residual char.

“We expect that the presented method might also be applicable at an industrial scale, although this is yet to be validated. However, the necessary procedures are already well established,“ Schuhmann says. “A mixture of catalyst and polymer could be sprayed on an electrode surface, which is then transferred into an oven.” The team at the Center for Electrochemical Sciences has already tested this method at laboratory scales.

This story is adapted from material from Ruhr-Universität Bochum, with editorial changes made by Materials Today. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent those of Elsevier. Link to original source.