A material that mimics the organs targeted by autoimmune cells could draw these cells away from vulnerable body tissues.

The military strategy of drawing fire towards decoy targets is showing promise as a way to treat autoimmune diseases. These diseases arise when the immune system wrongly identifies the body’s own tissues as foreign. The resulting self-destructive immune attack causes such conditions as multiple sclerosis (MS), rheumatoid arthritis and many others.

“We have built implantable biomaterials that mimic the tissue under autoimmune attack,” says Cory Berkland of the research team at the University of Kansas,United States, who report their procedure in the journal Biomaterials.

Current treatments for autoimmune diseases suppress the immune system to dampen down the attack on the body’s own tissue. This can slow and limit the autoimmune destruction, but it comes at the cost of leaving patients more vulnerable to infection, alongside other undesirable side effects.

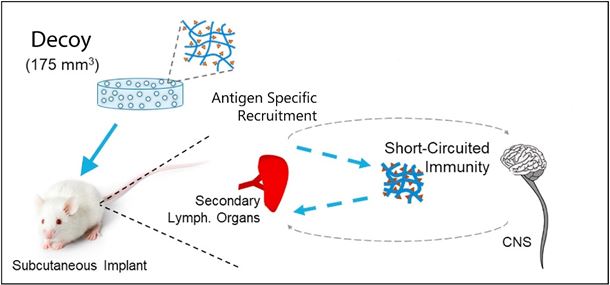

The researchers are exploring their alternative Antigen-Specific Immune Decoy (ASID) approach using mice suffering from autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), a condition that serves as a model for MS in humans.

In MS, the immune system attacks "myelin" – the sheath of fats and proteins that surrounds and electrically insulates nerves in the brain, spinal cord and optic nerves.

The decoys designed by the researchers consist of small parts of proteins – the "antigens" – chosen to mimic the proteins targeted by the autoimmune attack, carried on a scaffold of the inert protein collagen.

This decoy material was implanted beneath the skin of four mice with EAE. It was also given to healthy mice to act as a control and check for any undesired effects.

The EAE was “highly suppressed”, with none of the four mice showing any of the otherwise expected limb paralysis. Two of the mice also never developed any characteristic symptoms of EAE.

The decoys primarily served to attract autoimmune cells to the decoy during the trafficking process that would otherwise take them to the brain and spinal cord. The authors say the decoys “exhaust” the intercepted cells by interacting with them.

As an unexpected bonus, the mice seem protected against a relapse of their condition, even after the decoy materials had been reabsorbed into the bodies' tissues and degraded.

“We thought the disease would re-emerge, much like a relapse observed in untreated mice," says Berkland, “yet it didn’t.”

Berkland attributes this success in interfering with cell transport systems to his background as a bioengineer. “There are great researchers diving deep into immunological mechanisms and pathways, but engineers often bring a different vantage point,” he comments. This engineering perspective led his research group to focus on the bulk transport of cells, rather than the molecular events within them.

The successful small-scale trials must now be built on and refined to eventually lead to tests on humans and hopefully clinical trials.

The researchers also foresee using the decoys in diagnosis and monitoring the course of disease. If the decoys can amplify the early signs of autoimmune attack, and signal that process, they might allow diseases such as MS to be detected and treated earlier than is currently possible. And the level of response to the decoys might indicate the extent of disease progression.

Article details:

Berkland, Cory J. et al.: “Antigen-specific immune decoys intercept and exhaust autoimmunity to prevent disease,” Biomaterials (2019)