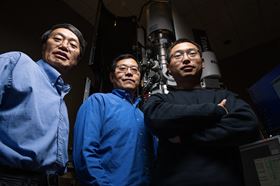

(Left to right) PNNL scientists Chongmin Wang, Wu Xu and Yang He with the specially modified environmental transmission electron microscope they used to capture images and video of growing whiskers inside a lithium battery. Photo: Andrea Starr/PNNL.

(Left to right) PNNL scientists Chongmin Wang, Wu Xu and Yang He with the specially modified environmental transmission electron microscope they used to capture images and video of growing whiskers inside a lithium battery. Photo: Andrea Starr/PNNL.Scientists have uncovered the root cause of the growth of needle-like structures – known as dendrites and whiskers – that plague lithium batteries, sometimes causing a short circuit, failure or even a fire.

The team, led by Chongmin Wang at the US Department of Energy's Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL), has shown that the presence of certain compounds in the electrolyte – the liquid material that makes a battery's critical chemistry possible – prompts the growth of dendrites and whiskers. The scientists hope their discovery, which they report in a paper in Nature Nanotechnology, will lead to new ways to prevent the growth of dendrites and whiskers by manipulating the battery's ingredients.

Dendrites are tiny, rigid, tree-like structures that can grow inside a lithium battery; their needle-like projections are called whiskers. Both dendrites and whiskers can cause tremendous harm; notably, they can pierce a structure known as the separator inside a battery, much like a weed can poke through a concrete patio or a paved road. They also increase unwanted reactions between the electrolyte and the lithium, speeding up battery failure. Dendrites and whiskers are holding back the widespread use of lithium-metal batteries, which have a higher energy density than their commonly used lithium-ion counterparts.

The PNNL team found that the origin of whiskers in a lithium-metal battery lies in a structure known as the solid-electrolyte interphase (SEI), a film where the solid lithium surface of the anode meets the liquid electrolyte. Further, the scientists pinpointed a prime culprit in the growth process: ethylene carbonate, an indispensable solvent added to the electrolyte to enhance battery performance. It turns out that ethylene carbonate leaves the battery vulnerable to damage.

The team's findings include videos that show the step-by-step growth of a whisker inside a nanosized lithium-metal battery specially designed for the study. These videos reveal that a dendrite begins when lithium ions start to clump, or ‘nucleate’, on the surface of the anode, forming a particle that signifies the birth of a dendrite. The structure grows slowly as more and more lithium atoms glom on, growing the same way that a stalagmite grows up from the floor of a cave. The team found that the energy dynamics on the surface of the SEI push more lithium ions into the slowly growing column. Then, suddenly, a whisker shoots forth.

It wasn't easy for the scientists to capture the action. To do so, they had to integrate an atomic force microscope (AFM) with an environmental transmission electron microscope (ETEM), a highly prized instrument that allows scientists to study an operating battery under real conditions. The scientists used the AFM to measure the tiny force of the whisker as it grew, by pushing down on the tip of the whisker with the cantilever of the AFM.

This revealed that the level of ethylene carbonate directly correlates with dendrite and whisker growth. The more of the material the team put in the electrolyte, the more the whiskers grew. The scientists experimented with the electrolyte mix, changing ingredients in an effort to reduce dendrites. Some changes, such as the addition of cyclohexanone, prevented the growth of dendrites and whiskers.

"We don't want to simply suppress the growth of dendrites; we want to get to the root cause and eliminate them," said Wang, a corresponding author of the paper. "We drew upon the expertise of our colleagues who have expertise in electrochemistry. My hope is that our findings will spur the community to look at this problem in new ways. Clearly, more research is needed."

Understanding what causes whiskers to start and grow will lead to new ideas for eliminating them or at least controlling them to minimize damage, added first author Yang He. He and the team also tracked how whiskers respond to an obstacle, either buckling, yielding, kinking or stopping. A greater understanding could help clear the path for the broad use of lithium-metal batteries in electric cars, laptops, mobile phones and other areas.

This story is adapted from material from the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, with editorial changes made by Materials Today. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent those of Elsevier. Link to original source.