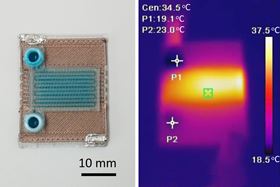

One of the novel self-heating microfluidic devices. Image courtesy of Luis Fernando Velásquez-García and Jorge Cañada Pérez-Sala.

One of the novel self-heating microfluidic devices. Image courtesy of Luis Fernando Velásquez-García and Jorge Cañada Pérez-Sala.Researchers at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have used 3D printing to produce self-heating microfluidic devices, demonstrating a technique that could someday be used to rapidly create cheap, yet accurate, tools to detect a host of diseases.

Microfluidics – miniaturized machines that manipulate fluids and facilitate chemical reactions – can be used to detect disease in tiny samples of blood or fluids. At-home test kits for Covid-19, for example, incorporate a simple type of microfluidic.

But many microfluidic applications involve chemical reactions that must be performed at specific temperatures. These more complex microfluidic devices, which are typically manufactured in a clean room, are outfitted with heating elements made from gold or platinum using a complicated and expensive fabrication process that is difficult to scale up.

As an alternative approach, the MIT team used multimaterial 3D printing to create self-heating microfluidic devices with built-in heating elements, through a single, inexpensive manufacturing process. They generated devices that can heat fluid to a specific temperature as it flows through microscopic channels inside the tiny machine.

Their technique is customizable, so an engineer could create a microfluidic device that heats fluid to a certain temperature or given heating profile within a specific area of the device. This low-cost fabrication process requires about $2 of materials to generate a ready-to-use microfluidic.

The process could be especially useful in creating self-heating microfluidics for remote regions of developing countries where clinicians may not have access to the expensive lab equipment required for many diagnostic procedures.

“Clean rooms in particular, where you would usually make these devices, are incredibly expensive to build and to run,” says Luis Fernando Velásquez-García, a principal scientist in MIT’s Microsystems Technology Laboratories (MTL). “But we can make very capable self-heating microfluidic devices using additive manufacturing, and they can be made a lot faster and cheaper than with these traditional methods. This is really a way to democratize this technology.”

Velásquez-García developed this new fabrication process with Jorge Cañada Pérez-Sala, an electrical engineering and computer science graduate student. It takes advantage of a technique called multimaterial extrusion 3D printing, in which several materials are squirted through the printer’s many nozzles to build a device layer-by-layer. The process is monolithic, which means the entire device can be produced in one step on the 3D printer, without the need for any post-assembly.

To create self-heating microfluidics, the researchers used two materials – a biodegradable polymer known as polylactic acid (PLA) that is commonly used in 3D printing, and a modified version of PLA. The modified PLA has copper nanoparticles mixed into the polymer, which converts this insulating material into an electrical conductor. When an electrical current is fed into a resistor composed of this copper-doped PLA, energy is dissipated as heat.

“It is amazing when you think about it because the PLA material is a dielectric, but when you put in these nanoparticle impurities, it completely changes the physical properties,” says Velásquez-García. “This is something we don’t fully understand yet, but it happens and it is repeatable.”

Using a multimaterial 3D printer, the researchers fabricate a heating resistor from the copper-doped PLA and then print the microfluidic device, with microscopic channels through which fluid can flow, directly on top in one printing step. Because the components are made from the same base material, they have similar printing temperatures and are compatible. Heat dissipated from the resistor will then warm fluid flowing through the channels in the microfluidic.

In addition to the resistor and microfluidic, they use the printer to add a thin, continuous layer of PLA that is sandwiched between them. It is especially challenging to manufacture this layer because it must be thin enough so heat can transfer from the resistor to the microfluidic, but not so thin that fluid could leak into the resistor.

The resulting device is about the size of a US quarter and can be produced in a matter of minutes. Channels about 500µm wide and 400µm tall are threaded through the microfluidic to carry fluid and facilitate chemical reactions.

Importantly, the PLA material is translucent, so fluid in the device remains visible. Many processes rely on visualization or the use of light to infer what is happening during chemical reactions.

The researchers used this one-step manufacturing process to generate a prototype that could heat fluid by 4°C as it flowed between the input and the output. This customizable technique could allow them to make devices that would heat fluids in certain patterns or along specific gradients.

“You can use these two materials to create chemical reactors that do exactly what you want,” Velásquez-García says. “We can set up a particular heating profile while still having all the capabilities of the microfluidic.”

However, one limitation comes from the fact that PLA can only be heated to about 50°C before it starts to degrade. Many chemical reactions, such as those used for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests, require temperatures of 90°C or higher. And to precisely control the temperature of the device, researchers would need to integrate a third material that enables temperature sensing.

In addition to tackling these limitations in future work, Velásquez-García wants to print magnets directly into the microfluidic device, for chemical reactions that require particles to be sorted or aligned.

At the same time, he and his colleagues are exploring the use of other materials that could reach higher temperatures. They are also studying PLA to better understand why it becomes conductive when certain impurities are added to the polymer.

“If we can understand the mechanism that is related to the electrical conductivity of PLA, that would greatly enhance the capability of these devices, but it is going to be a lot harder to solve than some other engineering problems,” he adds.

This story is adapted from material from MIT, with editorial changes made by Materials Today. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent those of Elsevier. Link to original source.