Researchers from the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) have increased the fatigue threshold of particle-reinforced rubber, developing a new, multiscale approach that allows the material to bear high loads and resist crack growth over repeated use. This approach could not only increase the longevity of rubber products such as tires but also reduce the amount of pollution from rubber particles shed during use. The researchers report their work in a paper in Nature.

Naturally occurring rubber latex is soft and stretchy. For a range of applications, including tires, hoses and dampeners, rubbers are reinforced by rigid particles, such as carbon black and silica. Since their introduction, these particles have greatly improved the stiffness of rubbers, but not their resistance to crack growth when the material is cyclically stretched, a measurement known as the fatigue threshold.

In fact, the fatigue threshold of particle-reinforced rubbers hasn’t improved much since it was first measured in the 1950s. This means that even with improvements to tires that increase wear resistance and reduce fuel consumption, small cracks can still shed large amounts of rubber particles into the environment, which cause air pollution for humans and accumulate into streams and rivers.

In previous research, a team led by Zhigang Suo, professor of mechanics and materials at SEAS, markedly increased the fatigue threshold of rubbers by lengthening polymer chains and densifying entanglements. But how about particle-reinforced rubbers?

In this study, the team added silica particles to their highly entangled rubber, thinking the particles would increase the stiffness but not affect the fatigue threshold, as commonly reported in the literature. But they were wrong.

“It was quite a surprise,” said Jason Steck, a former graduate student at SEAS and co-first author of the paper. “We did not expect adding particles would increase the fatigue threshold, but we discovered that it increased by a factor of ten.” Steck is now a research engineer at GE Aerospace.

In the Harvard team’s material, the polymer chains are long and highly entangled, while the particles are clustered and covalently bonded to the polymer chains.

“As it turns out,” said Junsoo Kim, a former graduate student at SEAS and co-first author of the paper, “this material deconcentrates stress around a crack over two length scales: the scale of polymer chains and the scale of particles. This combination stops the growth of a crack in the material.” Kim is now an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at Northwestern University.

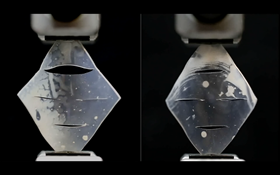

The team demonstrated their approach by cutting a crack in a piece of their material and then stretching it tens of thousands of times. In their experiments, the crack never grew.

“Our approach of multiscale stress deconcentration expands the space of material properties, opening doors to curtailing polymer pollution and building high-performance soft machines,” said Suo, senior author of the paper.

“Traditional approaches to design new elastomeric materials missed these critical insights of using multiscale stress deconcentration to achieve high-performance elastomeric materials for broad industrial uses,” said Yakov Kutsovsky, an expert in residence at the Harvard Office of Technology Development and a co-author of the paper. “Design principles developed and demonstrated in this work could be applicable across a wide range of industries, including high-volume applications such as tires and industrial rubber goods, as well as emerging applications such as wearable devices.”

This story is adapted from material from Harvard SEAS, with editorial changes made by Materials Today. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent those of Elsevier. Link to original source.

Cracks grow in the left sample while cracks in the right sample, made from the novel multiscale material, remain intact after 350,000 cycles. Image: Suo Group/Harvard SEAS.

Cracks grow in the left sample while cracks in the right sample, made from the novel multiscale material, remain intact after 350,000 cycles. Image: Suo Group/Harvard SEAS.